Sketching Atmospheres of the City

Aleksandra Ianchenko

In May 2022, I participated in an international research project entitled Measuring Urban Sustainability in Transition (MUST) that aims to define and measure indicators of sustainable development for Arctic cities. The project’s core participants include political scientists, economists, geographers, urban planners, architects, and climatologists who study the interconnectedness of natural, social and built urban systems in the Arctic. The project also develops collaborations with elected officials and representatives of the five case study cities and Indigenous communities as well as with practitioners from other fields including artists. The latter is facilitated by the ArtSLInK platform, MUST’s partner. Together with the academics and a mayor, I traveled to Luleå and Kiruna in Northern Sweden in Spring 2022.

Collaborating and working with academics is not a novel experience for me. For the past three years, I have been working on the project Public Transport as Public Space in European Cities: Narrating, Experiencing, Contesting (PUTSPACE) which brings together scholars from the disciplines of human geography, cultural and literary studies, and history. In collaboration with PUTSPACE members, I curated the mobile exhibition Rabbits&Rails.

I also continue working on my PhD thesis based on my art practice which includes performing in public space, filmmaking, painting, and drawing. I define my PhD project as artistic research at the intersection of studies on mobilities and atmospheres with a focus on trams as the most atmospheric means of urban public transport. One of my methods to study atmospheres and immediate sensory experiences on board trams as well as at tram stops is on-location sketching.

On-location sketching was a method I used during my trip to Sweden in order to sense and engage with the atmospheres of different sites in Luleå and Kiruna. A two-day sketching workshop became a part of the program and resulted in a number of interesting insights and wonderful drawings by MUST team members.

In the following text, I provide an improvised report about our collective sketching practice as well as about my individual fieldwork beginning with some theoretical and methodological considerations.

What is an atmosphere?

For our Urban Sketching workshop I suggested looking at an atmosphere or sense of place. An atmosphere is something we might feel in a certain situation or place as if it is something invisible spilled in the air. It can be difficult to define what this atmosphere is but we certainly feel it. Moreover, an atmosphere can affect the way we experience the place and how we behave. In its direct sense, the word “atmosphere” means a gaseous layer around the planet, yet Romantics in the 19th century used it in a metaphorical sense to describe a feeling or mood. However, as an elaborated theoretical concept, it emerged in the writings of German philosopher Gernot Böhme in the late 1990s.

He defines an atmosphere as a relationship between us as sensing subjects and the spatial situation in which we are physically present. An atmosphere combines the physical and sensorial configuration of a place with the feelings, emotions, and sensations of individuals together with their socio-cultural background, previous knowledge, and experiences.

The complexity of atmospheres poses methodological challenges: how can we study peoples’ experiences in relation to the sensory and material configuration of a place?

Scholars Shanti Sumartojo and Sarah Pink suggest employing creative and artistic approaches in conjunction with more traditional methods of participant observations or interviews. They define atmospheres as “a coming together of different and subjective ways of understanding a site or event, based on different memories, expectations or foreknowledge, sensory or bodily capacities, cultural understanding and familiarity and the immediate contingencies of the experience” (Sumartojo; Pink, 2019, 6).

Following their suggestion, I propose sketching in situ (also called on-location or observational drawing) as one of the artistic ways of studying atmospheres.

How can sketching be a method?

On-location sketching is a common practice among professional artists and enthusiasts, who together create a worldwide community of Urban Sketchers.

In academic fields, sketching in situ has gained popularity as a visual ethnography tool and a form of field notes. Speaking about the benefits of field sketching, Karina Kuschnir (2016) notes that the process of looking and selecting what to draw helps a sketcher-observer become more aware of the location. Similarly, Brice Sage (2018) calls observation drawings a form of attunement through which a person can get physically, emotionally, and sensorily attuned to the location. She points to the corporeal nature of on-site sketching when one is exposed to the site and its immediate atmospheres, both in metaphorical and meteorological senses.

Drawing itself is a bodily practice because we move our hand over paper connecting what we see with the way we draw it. In this sense, drawing as a process connects seeing, imagination and motion. Consequently, drawing as a result can be seen as not an image but as a trace of our hand’s movement. Sketching or making rapid drawings is faster than writing so it is possible to capture an immediate experience in the moment when it takes place. During fieldwork, when a variety of events unfolds in front of an observer, sketching can help her to outline and capture them in one hand’s movement. Anthropologist Tim Ingold says drawing “combines observation and description in a single gestural movement” (Ingold 2011, 222).

Of course, photography can also capture a moment, but sketching has its own advantages. First, it is easy to combine images with texts on one page where lines and words intertwine. Second, sketching allows one to pick objects and draw them separately from their background or combine them in a different manner than they exist in reality. Third, sketching allows expressing something which is not seen but felt in the site or imagined in its regard, something invisible yet palpable like atmospheres. In this sense, I agree with anthropologist and sketcher Michael Taussig that in field drawings “imagination and documentation coexist” (Taussig 2011, 31).

Sketching together: two-day workshop in Luleå

Photo by Aleksandra Ianchenko

These theoretical and methodological considerations about atmospheres and how to study them were introduced at the beginning of our two-day sketching workshop with the MUST team. Furthermore, I encouraged the workshop’s participants, who had little to no experience in drawing, to approach field sketching as a creative experiment with the aim of not making nice drawings but learning something new and expressing their feelings and impressions through drawing. In this regard, I share Tim Ingold’s idea that drawing is as natural as walking and dancing and does not always require training and skills. After all, as children, we were keen to draw without really knowing any rules or techniques.

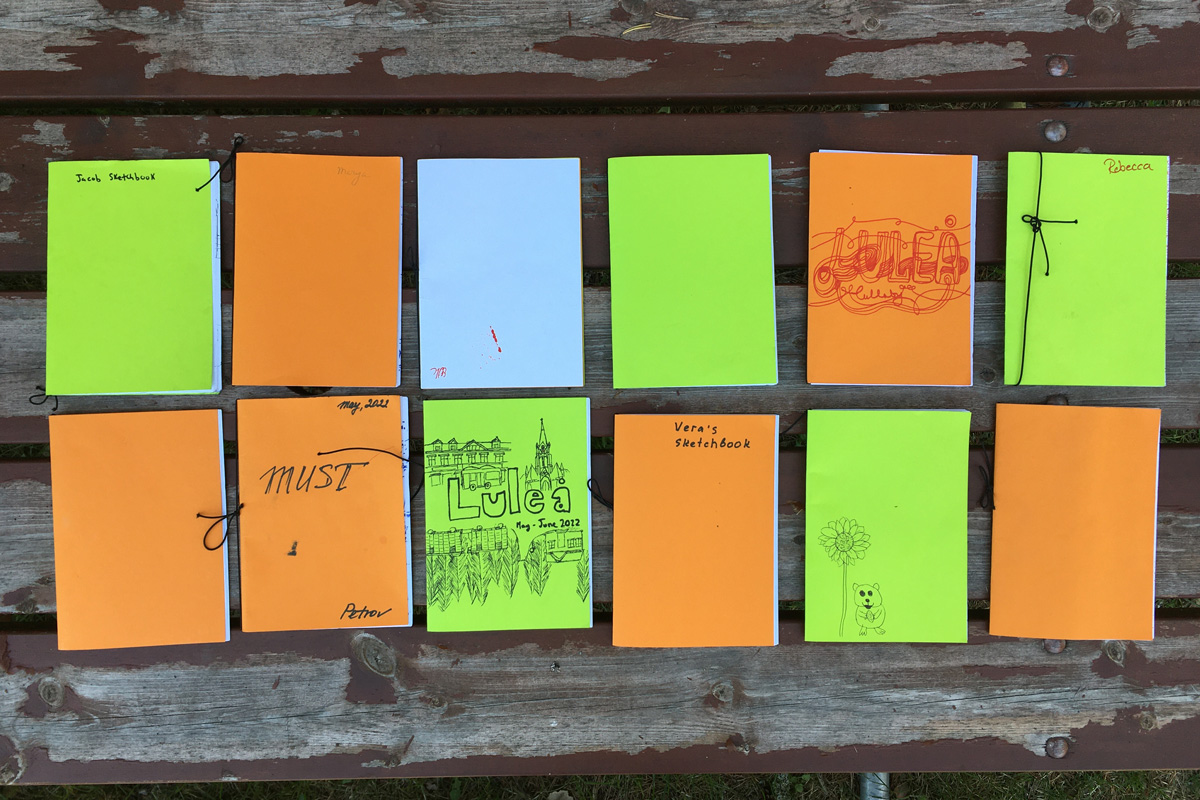

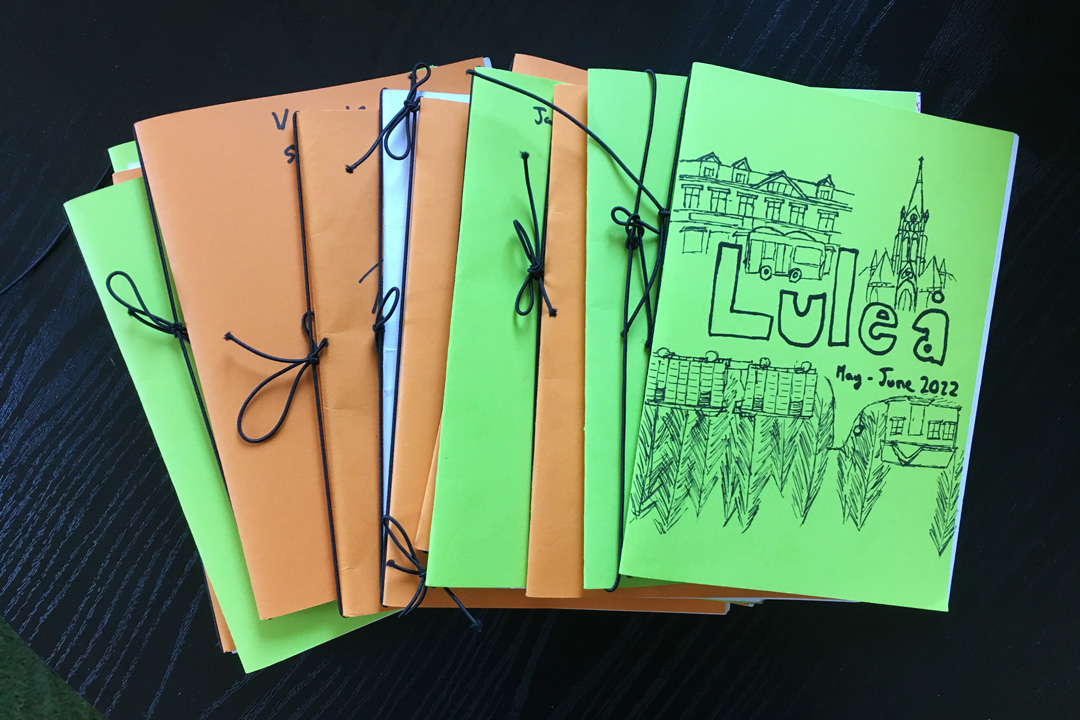

Drawing materials were also intended to liberate the participants from the fear of making mistakes. Borrowing an example from Kuschnir’s article, we made our own sketchbooks from plain A4 sheets of paper folded in half. The simple, relatively cheap, and easily replaceable paper was meant to remove the fear of spoiling a page with ostensibly inaccurate drawings.

Furthermore, blue, red, and black markers were meant to encourage participants not to make preliminary drawings with pencils and erasers but to express directly what came to their mind. In this sense, the marker strokes would be direct records of first impressions and intentions to draw.

Photo by Aleksandra Ianchenko

Photo by Aleksandra Ianchenko

After the theoretical part and with newly made sketchbooks, we went to Storgatan, a central pedestrian zone in Lulea. We intentionally did not collect any information about the street beyond the general knowledge that it is a center of shopping and leisure activities. We intended to draw what we saw and felt on the street but not what we knew about it. The street offered enough space for our large group and the sunny and warm weather was benevolent for our outdoor practice. Furthermore, our workshop happened on a public holiday, so the street was full of people coming to shop, visit cafes, or simply take a stroll. Spreading along the street, participants worked on their drawings for more than an hour. Some of them drew sitting on benches, others went back and forth along the street searching for objects and scenes to draw. Some of them finished their drawings quickly and went to enjoy a cup of coffee on the sunny terraces.

Photo by Aleksandra Ianchenko

Photo by Aleksandra Ianchenko

Photo by Aleksandra Ianchenko

Photo by Aleksandra Ianchenko

Photo by Vera Kuklina

Photo by Aleksandra Ianchenko

Photo by Aleksandra Ianchenko

Photo by Aleksandra Ianchenko

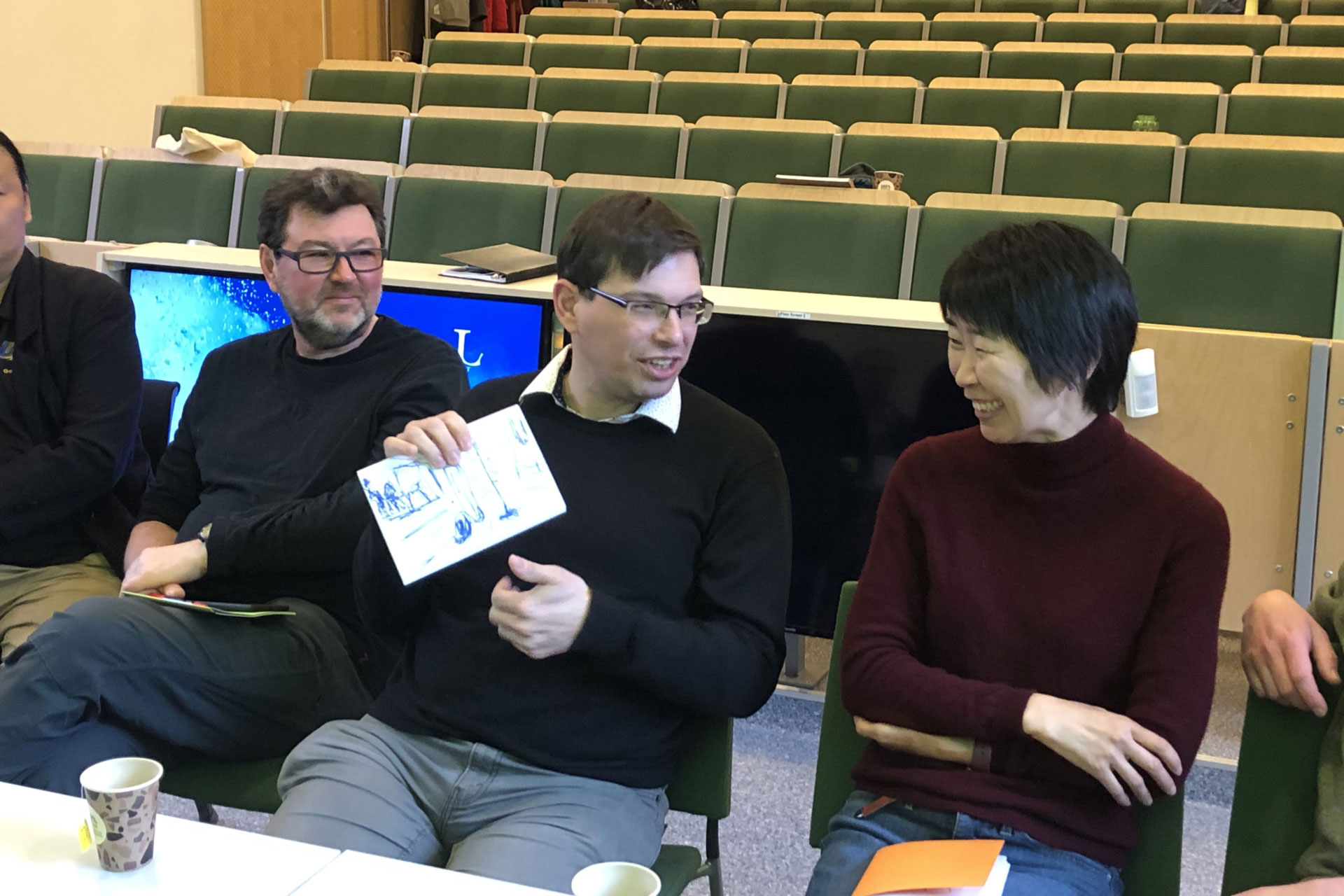

On the next day, we gathered to discuss our fieldwork and show our drawings. Sitting around the table, we shared our experiences of sketching on Storgatan. The atmosphere of our gathering was cheerful: we laughed a lot and showed our sketchbooks noticing similarities and differences among our drawings. Although for most of the group sketching was an entirely new experience, participants were open to talking about it and sharing what was difficult or pleasant for them. If some participants enjoyed the process, forgetting about the passage of time (“I could have been easily robbed! I was so deep into the process!”), others felt uncomfortable being challenged with the unusual activity without clear instructions on what to draw and how. The different understandings of drawing are expressed in short diamond poems which participants wrote at the end of the discussion. According to their poems, drawing can be “humiliating” and “challenging” but “creative” and “rewarding”. It requires “watching” and “sitting”, “feeling” and “immersing” but eventually leads to “success”.

Photo by Zoe Garbis

Photo by Zoe Garbis

Photo by Zoe Garbis

Photo by Zoe Garbis

Photo by Zoe Garbis

Photo by Zoe Garbis

Looking at drawings after our workshop, I noticed that despite their many differences, they can be divided into four categories. First, many participants sensed and tried to express the shape of the street, drawing it in perspective and conveying an impression of a rather wide street, where there is a lot to see. Second, some participants focused on buildings and their facades which frame the street from both sides. With their different architectural styles and shops and cafes on the first floors, buildings certainly contribute to the appeal of Storgatan as a central street. The third category of drawings features specific objects, such as benches, signs, trees, trash bins, among others. In the fourth group of drawings, some participants tried to capture passersby, admitting that human figures are the most difficult to draw.

The street in perspective

Buildings along Storgatan

The dearth of drawing experience fueled creativity when participants had to invent original ways of depicting something they lacked the skill to portray. For instance, one participant drew a chain of dots as a signifier of people walking along the street and their traces. She also drew three cups of coffee on the table and a shining sun as a symbol of pleasant conversation among three people in a cafe on a warm sunny afternoon.

Another participant drew a similar scene in a cafe but with human figures whose heads were surrounded by small dots and circles which signified their conversations. Swedish language, unfamiliar to the participant, became to her a melody of sounds that she perceived and visualized as something round.

The similarity in drawings by different people points to the affective qualities of atmospheres when many people perceive the same atmosphere similarly. That is why many would call the same cafe cozy and the same street charming and pleasant for walking.

Looking at our drawings, we can define what contributed to the atmosphere of Storgatan when we were drawing there. It is a configuration of the street framed by different buildings with stores and cafes on the first floor; the sunny weather and the holiday mood of people enjoying their walks and chats over coffee; words and signs in a foreign-for-us language which conveys no meanings beyond visual and aural impressions, etc. I hope that this atmosphere can be sensed by looking at our drawings which are summarized in this video.

Wandering with a sketchbook in Luleå and Kurina

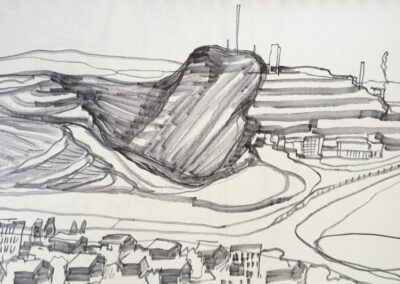

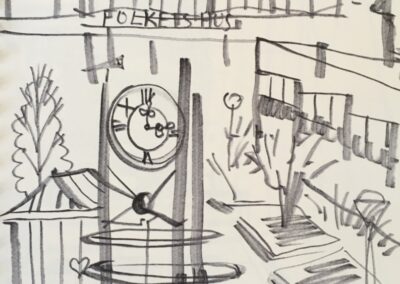

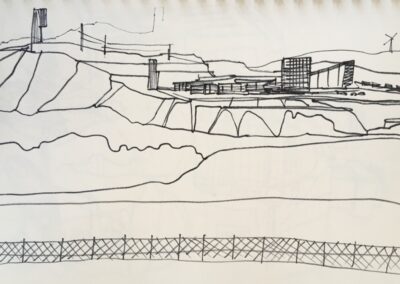

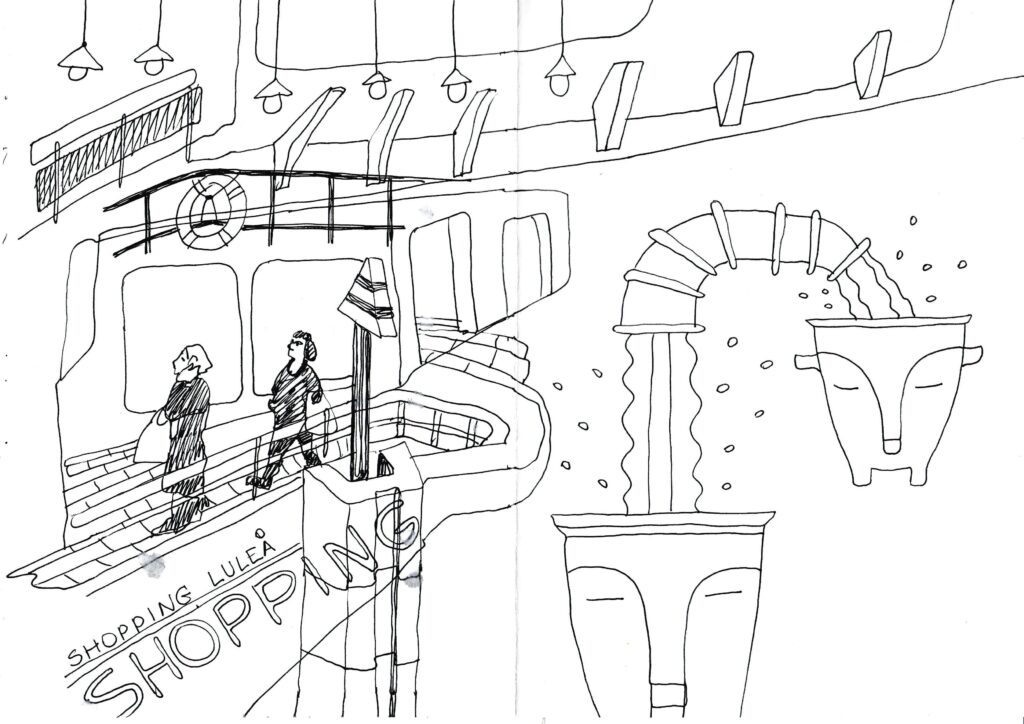

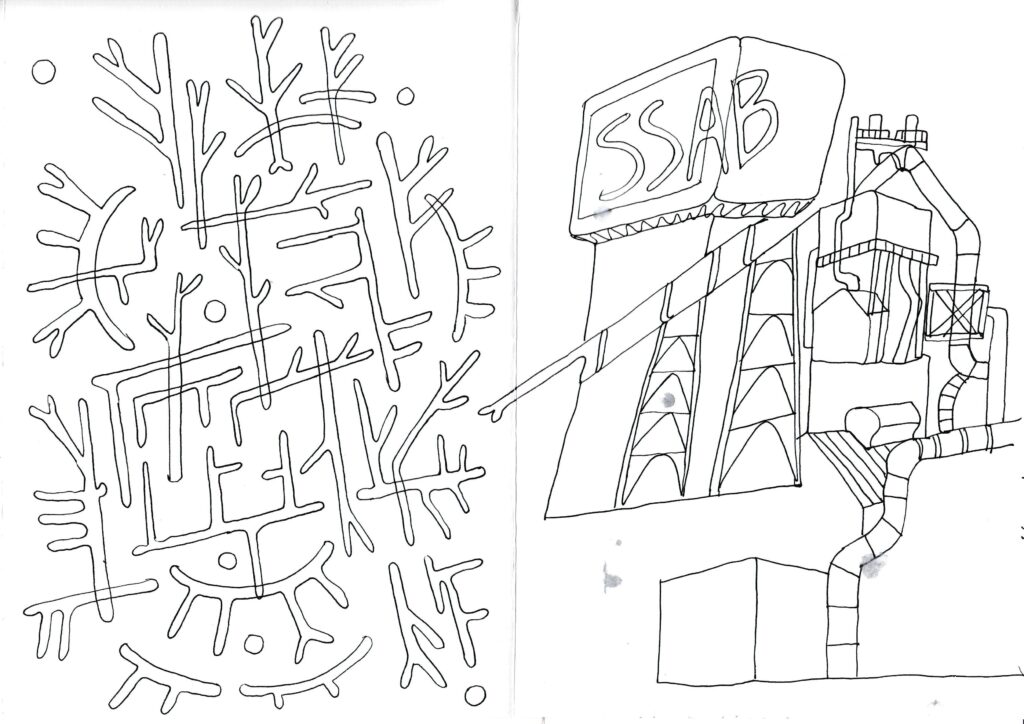

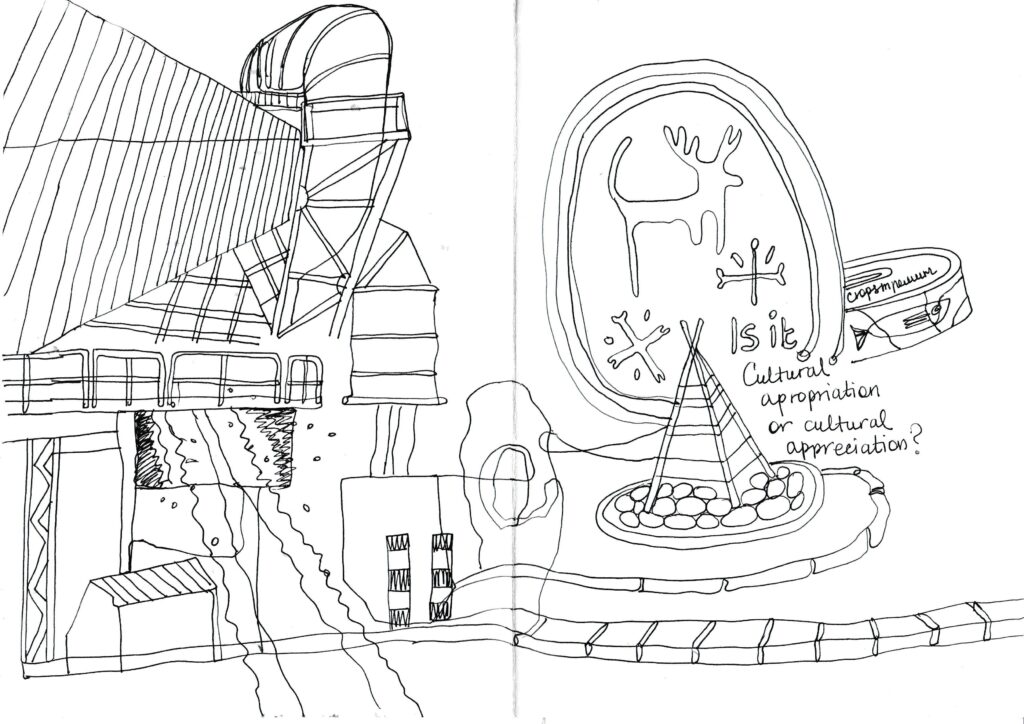

For my individual sketching experiments in Luleå, I used a technique of laconic linear drawing in my own hand-made sketchbook of folded A4 sheets. I drew one sketch after another on the paper, but when I unfolded it, the separate sketches on the same page came into an interesting dialogue with each other. For instance, my sketch of a huge steel plant is now on the same page as a peaceful river view. For me, the juxtaposition points to the peculiarity of the city where heavy industry stands next to wild nature. Or the same steel plant now shares the page with abstract patterns which resemble those drawn by Saami, the Indigenous people in Northern Sweden. This combination directs my thoughts to the tense dialogue (and its absence at times) between different worldviews. Such mixtures of scenes were not directly visible in the locations I drew, yet they appeared in my drawings as a reflection of what I sensed in the city and what I learned about its past, present, and desirable future. Visual impressions and new knowledge about the city, my memories from my adolescent years spent in a similar town built around a metallurgical plant in Eastern Siberia, and my bodily sensation of the cool polar summer contributed to the atmospheres I outlined in my sketches.

Drawings by Aleksandra Ianchenko

For sketching in the northernmost Swedish city of Kiruna, I chose a different tool. To achieve some interesting effects and textures, I used a marker that was nearly dry. Later I realized how this tool resonates with the city itself, half of which is being built, while the other half is being moved or removed. With this vanishing marker, I drew both the process of constructing buildings in the new, becoming city center as well as abandoned houses sentenced to removal or replacement. As the line of the marker slowly disappears, the old part of the city is giving way to the new one due to inexorable progress.

However, there was enough ink in the marker to draw several scenes of the mining operation that looms over the city and its enormous pit. The mine is Kiruna’s main industry and employer. Relentless iron ore extraction expanded the pit to the point that it now threatens the stability of the old city center. The impending collapse of the old downtown led to an extraordinary decision to build a new center and move there some of the buildings which have historical and cultural meanings. Other buildings will be demolished. I felt the urge to capture this fleeting moment of transition. My drawings capture the dynamic of the construction process of new buildings and the stillness of emptied houses. Yet I sense the movement in both sites as if they are heading in opposite directions – either towards being demolished or completed – but certainly away from the growing pit.

Ten days of my fieldwork in Sweden were full of exciting lectures and excursions, interesting meetings and discussions which I was happy to experience in the great company of the MUST team. I enjoyed the productive dynamics and friendly atmosphere in our group and hope that the sketching workshop contributed to the general mood of the project. I also hope that the workshop gave participants the experience of doing something artistic and something outside of regular routine as well as of using drawing not as a memetic but an expressive tool. I hope that this experience will be somehow useful for them in the future as it was for one participant who kept drawing in her sketchbook until the end of the Swedish field trip.

My sketches from Luleå and Kiruna have become the first step in a three-fold methodology of studying atmospheres which I borrow from Sumartojo and Pink. They suggest three stages: knowing in, about and through atmospheres. The first stage is conducting observations directly in the atmosphere, the second stage is interpreting the field notes from the first stage according to the data about this atmosphere from secondary sources, whereas the third stage is a wider theoretical or practical solution based on the gained knowledge. Following this methodology, I place my sketches in the first stage, while the second step will be creating elaborated large-scale graphic works to be presented at the exhibition which will become a third stage of thinking through the atmospheres of two cities in the Swedish north.

References:

Böhme, Gernot. 2017. The Aesthetics of Atmospheres. Routledge.

Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive. Essays on movement, knowledge and description. Routledge.

Kuschnir, Karina. 2016. “Ethnographic drawing: Eleven benefits of using a sketchbook for fieldwork”. Visual Ethnography, 5(1), pp. 103–134.

Taussig, Michael T. 2011. I swear I saw this: drawings in fieldwork notebooks, namely my own. The University of Chicago Press.

Sage, Brice. 2018. “Situating skill: contemporary observational drawing as a spatial method in geographical research”. Cultural Geographies 25(1), pp. 135–158.

Sumartojo, Shanti; Pink, Sarah. 2019. Atmospheres and the Experiential World. Theory and Methods. Routledge.